Every election would be competitive

Every district would have a competitive race every cycle.

The major parties would have incentives to recruit a diverse slate of candidates, giving voters choices beyond whether their representative identifies as a Republican or Democrat.

Third parties and independent candidates would play a more meaningful role.

Incumbents would be more accountable to their voters.

Proportional ranked choice voting makes every vote very powerful. Under this system, every district elects several winners, and both major parties are competitive in all of them. That means that in every district, the number of seats each party wins depends entirely on the votes cast — rather than how district lines were drawn. In this system, every vote is valuable in every election. The rankings ensure that every vote counts in the most powerful way possible: Votes for candidates who cannot win or don’t need them will count for their next choices instead. No more wasted votes, and no more safe districts.

In short, proportional ranked choice voting creates so many opportunities for competition that every voter in every district can expect to be part of a competitive election every cycle. Instead of a small handful of swing districts deciding control of the U.S. House of Representatives, all voters would be part of that national decision.

Now, not every single candidate will run in a competitive election every cycle. Reelection rates on average probably will not change much, not because any incumbent is in a “safe seat,” but because incumbents who have earned the support of their constituents can be confident that they will withstand challenges. But when several winners are elected in a district, it takes only one vulnerable candidate to make the entire district competitive.

In single-winner plurality elections, there is only one opening for competition: a race between a Republican and a Democrat in a district that is closely divided between voters who prefer Republicans and those who prefer Democrats. In practice, this is rare: In 2020, analysts rated at least 300 of 435 seats safe for the incumbent party. Reforming the process by which we hold primary elections and draw district lines, as well as implementing ranked choice voting, would increase competition at the margins, but those reforms would not challenge the overall dominance of safe seats in winner-take-all systems, and would therefore fall short of providing the kind of competition necessary for a healthy democracy.

In this chapter, we consider the impact that proportional ranked choice voting would have on three kinds of competition: that between the major parties, between candidates of the same major party, and from outside the two major parties. Finally, we consider the distinction between competition and turnover and what the new system would mean for incumbents.

Competition between the two major parties

Single-winner districts are usually categorized as “safe,” “swing,” or “lean” based on the degree to which voters are divided between those who prefer Republicans and those who prefer Democrats. To classify as a swing seat, usually 47 to 53 percent of voters must favor one or the other major party. In other words, only a narrow band of partisanship, however measured, makes a single-winner district competitive. Mathematically, most district maps likely have few competitive districts. This plays out in practice: More than 80 percent of districts are safe for one political party in every U.S. House election.

With proportional ranked choice voting, voters are represented in proportion to their share of the vote. Districts that elect three winners allow a party to win a seat if their nominee earns more than 25 percent of the votes cast. Districts would be two-party competitive anywhere either party has support from at least 22 percent of the voters, which is almost everywhere.

In other words, proportional ranked choice voting would essentially make the United States a “swing” country, and control of the U.S. House would be legitimately up for grabs every two years. Incumbents would be far more accountable to their voters on the campaign trail and in office. They would need to cater their campaigns to their constituents’ needs and govern according to those constituents’ wishes. Ultimately, this would mean that laws supported by the public would be more likely to pass the U.S. House, and that the public would have a greater say in law and policy that shapes their lives.

In 2021, multi-winner district maps were drawn for every state using the guidelines laid out in the Fair Representation Act. No attempt was made to draw competitive districts. The only goal was to keep counties, cities, and other communities of interest together. A sample of these maps is available in Appendix B, and all of them can be viewed online at www.oursharedrepublic.org.

These demonstration maps showed that both major parties would be competitive in every single district. The most heavily partisan district was the one electing five seats and encompassing lower Manhattan and Brooklyn in New York City, at 86 percent Democratic, but even that puts Republicans less than three percentage points away from a seat, making them very competitive. Manhattan may be considered solid blue, but over half a million Republican voters live there; with proportional ranked choice voting, those voters would finally have a say in our system. A Manhattan Republican would probably vote differently than an Arkansas Republican, especially on issues affecting their urban constituents; we would all benefit from that perspective, as well as the myriad other perspectives multi-winner districts would bring to the table.

This is not merely theoretical. From 1870 to 1980, Illinois elected its state House of Representatives with a semi-proportional method known as cumulative voting, exclusively in three-winner districts. Voters had three votes, and they could cast all three votes for one candidate or divide them up, which ensured that a group with at least 25 percent of the vote could always elect at least one member.

Though this system (which tends to lead to more wasted votes than proportional ranked choice voting) falls short of full representation, it did make almost every district two-party competitive. As a result, in heavily Democratic Cook County (including Chicago), Republicans earned a proportional number of seats. Meanwhile, in the more rural “collar counties” outside of Cook County, Democrats earned a proportional number of seats as well. The system made geography matter less and votes matter more.

Every single proportional ranked choice voting election for at least three seats should result in the election of at least one Democrat and at least one Republican. Democrats would contest and win seats in ruby red places like Arkansas and the Texas panhandle, while Republicans would contest seats and win in sky blue areas like coastal California and Chicago.

What’s more, the parties would not only win more seats in what are currently considered safe districts, but they would also contest more races in these areas. If a party earned one seat in one cycle, it might try to win two in the next one. Because the threshold to win each additional seat is relatively low, more seats are not completely out of reach.

Under the cumulative voting system that Illinois used, parties generally did not try to win additional seats because fielding an additional candidate could split a common base of support, yielding fewer votes for each nominee. With proportional ranked choice voting, however, additional candidates can run together as a team, urging voters to rank them all. The round-by-round count resolves vote splits by eliminating the weakest candidates and looking to their second-choice support. To draw more voters to their slate, such teams do best by keeping their team large and diverse, and by campaigning directly to voters. In effect, every election would have a dynamic field of candidates and a genuine choice between and within the parties. Every voter, regardless of age, race, gender, or income would have the opportunity to vote for and help elect someone genuinely representative of their community.

Intraparty competition

Another source of competition likely to occur in every election year and in every district is competition between candidates of the same political party. A district electing three winners would feature at least two nominees from each party in the general election. With proportional ranked choice voting, voters vote directly for candidates, giving them a choice not only between parties but also between each party’s multiple nominees. That is, a voter who likes Democrats could not only vote for Democrats but also influence which Democrats win and which don’t.

Intraparty competition will look different from competition between parties because co-partisans will likely run together as a team. For example, if a race has three Republican candidates, each would do best by encouraging voters to rank them highest followed by the other two Republicans. The Republican team would want the whole Republican vote to be pooled, thereby maximizing the number of fellow Republicans who win. Of course, whether voters actually do that is up to them.

At the same time, each nominee will also want to differentiate themselves from their co-partisans in order to win as many first choices as they can. The simplest way to do that is geographically: Each nominee can campaign most heavily in the areas where voters know them. However, candidates can also differentiate themselves in other ways. If one Democratic nominee runs on a racial justice platform, another may want to emphasize labor issues, while a third focuses on climate and the environment. A diverse slate helps the party as a whole attract more voters and, at the same time, gives voters a more dynamic choice in the general election.

Presently, only four states use an election method that allows for intraparty competition in congressional general elections:[1] Louisiana, California, Washington, and (since 2022) Alaska. However, genuine intraparty competition, where two viable candidates of the same party compete in the general election, remains rare in California and Washington; when it does happen, it comes at the cost of any voices outside of a single major party in the general election.

Alaska is the sole place that may have genuine intraparty competition as a regular part of its congressional general elections because of its use of single-winner RCV in the four-candidate general election. The 2022 elections showed that this does represent a modest increase in competition, with the highest profile example being Alaska’s at-large congressional district, where Republicans Sarah Palin and Nick Begich competed both against each other and against incumbent Democrat Mary Peltola.

While multi-winner districts create intraparty competition by encouraging a diverse but usually well-aligned team, intraparty competition in a single-winner district is different. The election is, by definition, zero-sum: Only one nominee can win. That means that co-partisans campaign not as a team but as rivals. In Alaska, this meant that both Palin and Begich campaigned with mixed messages, both encouraging voters to “rank the red” and also directly competing against each other.[2]

Naturally, political parties avoid such contests wherever possible. The Democratic Party, for instance, gains nothing when Democrats spend money and resources running against other Democrats, which is partly why we see so few intraparty general elections in California and Washington.

Outside of the four states mentioned above, the most common source of intraparty competition in single-winner elections takes place in primary elections. Being “primaried” by a co-partisan is even a source of turnover and generally favors more ideological candidates because primary voters tend to be more ideological and tend to back more extreme candidates.

Under proportional ranked choice voting, incumbents would rarely lose in primaries, because parties would nominate multiple candidates in each multi-winner district, so challengers will run without directly challenging their co-partisan incumbents. In other words, challengers in primary elections would advance to the general election alongside incumbents.

For instance, if a five-winner district has two Democratic incumbents and three Republican incumbents, the Democrats would want to nominate at least three candidates if they want to gain at least one seat. In such a district, Democrats might be expected to nominate the two incumbents as well as a new Democratic candidate. That new candidate’s goal would not necessarily be to displace one of the other Democrats, but to increase the Democratic Party seat share by displacing the most vulnerable Republican. However, from time-to-time, doing so may result in voters voting in the new Democratic candidate even while they vote out one of the Democratic incumbents – it would be entirely up to the voters.

As the example illustrates, new challengers would only displace incumbents if they were genuinely more popular. Ireland’s use of proportional ranked choice voting suggests this would be a genuine source of competition and turnover. In Ireland, incumbents have lost to members of their own political party more often than to opponents from other parties.

The big question impacting how often candidates would compete with co-partisans is how political parties choose their nominees. Under current rules, states design their primary systems; some states have open primaries, others closed primaries, and a few do not use partisan primaries at all.

Experts offer various proposals about how to nominate candidates under proportional ranked choice voting. Under the Fair Representation Act, states would still have the right to design their primary systems, so long as all partisan primaries advance at least two candidates by proportional ranked choice voting.[3] Those rules would probably increase general election intraparty competition because each nominee would represent a distinct group of primary voters.

Some advocate for abolishing primary elections and instead giving each party full control over its nominations, as is the case in almost every other democratic country. That rule would probably improve party slate cohesion, but the party would still be incentivized to run a diverse slate of candidates in order to draw as many voters as possible. This has been the case in other countries with proportional representation, where parties usually try to run candidates representing different geographies and demographics. All told, proportional ranked choice voting would give voters genuine choices within and between political parties in the general election, no matter how nominees are selected.

Competition from outside the two major parties

In general, proportional systems facilitate multiparty rather than two-party systems. They do not themselves create multiparty systems, and some countries with proportional representation have two-party systems. However, single-winner districts suppress alternative political parties whereas multi-winner districts accommodate them.

Currently, political parties other than the Republicans and Democrats play almost no competitive role in congressional elections. In 2022, there was one district where an independent candidate came in second ahead of one of the two major parties: Montana’s 2nd, where Independent Gary Buchanan earned an impressive (for a non-major party candidate) 21 percent of the vote, but still lost by a 35 point margin in the safe Republican district.

No Independent or third-party candidate has been elected to the U.S. House since 2004. That year, Bernie Sanders of Vermont, an Independent who caucuses with the Democrats, was elected to the U.S. House; before Sanders, the last Independent to win congressional office was Frazier Reams of Ohio. He won in 1952. Third party candidates may run for other reasons, such as to elevate issues ignored by the two major parties, but they rarely serve as a genuine source of competition in congressional elections.

One reason why third parties so rarely achieve large vote shares is because they are seen as “spoilers”— a pejorative term for a third candidate who splits a common base of voters with a major party candidate, causing them to lose. For instance, a Republican in a left-of-center district might win a plurality of votes when the majority of voters are divided between a Democrat and a Green Party candidate; or a Democrat might win a plurality of votes when a conservative majority is divided between a Republican and a Libertarian. Third party candidates face accusations of being spoilers frequently – as when liberal media personalities Michael Moore and Bill Maher begged former Green Party presidential nominee Ralph Nader not to run for President again in 2004, for fear that his doing so would help re-elect George W. Bush.[4] Fear of “spoiling” an outcome discourages third candidates from running and, when they do run, it discourages people from supporting them.

But the spoiler issue is not the whole story. That problem should be mitigated by runoff elections or by single-winner ranked choice voting. Several states use either runoffs or ranked choice voting, but these systems have yet to spur more serious alternative parties. There are many reasons for this, but a big one is that when only a single candidate can win, the most serious candidates tend to seek the nomination of a major party rather than running outside the two-party system.

In political science, the “seat product model” estimates the effective number of political parties[5] that will win seats in a legislative assembly. Put simply, two variables tend to increase the number of political parties winning seats: the overall size of the assembly and the number of winners in each district.[6] Larger assemblies tend to feature more parties, as do assemblies elected in large multi-winner districts. According to the seat product model, about 2.8 effective parties should win seats in the U.S. House today. Under the Fair Representation Act, which would establish proportional ranked choice voting in districts electing between three and five winners, about 3.7 effective parties would win seats.

The seat product formula yields only an estimate; the actual result depends on many factors. The U.S. Senate and the Electoral College arguably both suppress the number of effective political parties. But because the estimated number of effective parties would jump under the Fair Representation Act, then that Act would make a genuine multi-party system feasible if voters want it.

Proportional systems are undoubtedly more open to competition from smaller political parties, but how much depends mostly on the election threshold, which determines how many votes are needed to win seats. In Germany, for example, if at least 5 percent of voters nationally vote for a party, that party will win seats.

Under proportional ranked choice voting, the election threshold is determined by the district magnitude: The more seats elected in a district, the lower the threshold. Under the rules for district magnitude in the Fair Representation Act,[7] just under half of the representatives would come from five-winner districts, which have an election threshold of just under 17 percent of the vote. That is higher than today’s third-party vote shares but low enough that, under the right circumstances, a serious candidate may be just as well off running under a new party label than seeking the nomination of a major party.

For example, a candidate may be able to win one of Utah’s four House seats by running as the nominee for a new anti-Trumpist conservative party. The threshold in a four-seat election is 20 percent of the vote, and, in 2016, Independent presidential candidate Evan McMullin earned almost 22 percent of the statewide vote. That kind of diversity may be hidden in many places in the country, on all sides of the political spectrum. We do not have the data to take this theory beyond speculation, but it provides a plausible path to representation of more than two parties in the House.

Even in districts with low district magnitudes, and even in places where candidates who run outside the two-party system cannot expect to win, proportional ranked choice voting would create new opportunities for competition from outside the two major parties. For example, in a three-winner district where a third-party candidate polls at 5 percent, many of the candidate’s backers will rank the major party candidates on their ballots, which incentivizes major party candidates to seek those voters’ backup support. This happens today in places with single-winner ranked choice voting. Under proportional ranked choice voting, those votes would be even more powerful, and this dynamic far more universal. If both major parties opposed some policy that had popular support among people, a third party could raise it and genuinely hold the major parties accountable – threatening their dominance unless they pay attention to what the voters want.

Competition versus turnover

An increase in competition, however, is not the same as an increase in incumbent turnover. An election is competitive if voters have a meaningful opportunity to affect the outcome. A voter in a five-winner district who helps change one seat is partaking in a competitive election, even if the other four candidates win comfortably.

Consequently, the rates at which incumbents lose their seats to challengers may stabilize over time and approach today’s rates. The difference is that those incumbents would not be safe because of district lines but rather because of their popularity. There would be no safe districts, but an incumbent could become reasonably safe by representing their voters well. If a representative earns the enduring support of a constituency that is larger than the election threshold, they will win re-election. With proportional representation, competition and stable representation can coexist.

An analysis of incumbent retention rates in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which elects its city council with proportional ranked choice voting, shows that incumbents win at about the same rate as other nearby cities that elect at-large candidates with a traditional winner-take-all method. Averaged over multiple election cycles, Cambridge has reelected about 91 percent of its incumbents per election, compared to 93 percent in Boston, 93 percent in Worcester, and 87 percent in Lowell.

The stability of incumbent reelection rates should alleviate the concerns of representatives who serve in safe seats today (that is, most of them) and worry that changing to proportional ranked choice voting will hurt their job prospects. When incumbents hear that a proportional system increases competition, they rightly worry about stability; but a key benefit of a proportional system is that it allows both competition and stability. Every vote will have much more power, but when representatives have earned the support of voters who know them, they have nothing to fear from the new system.

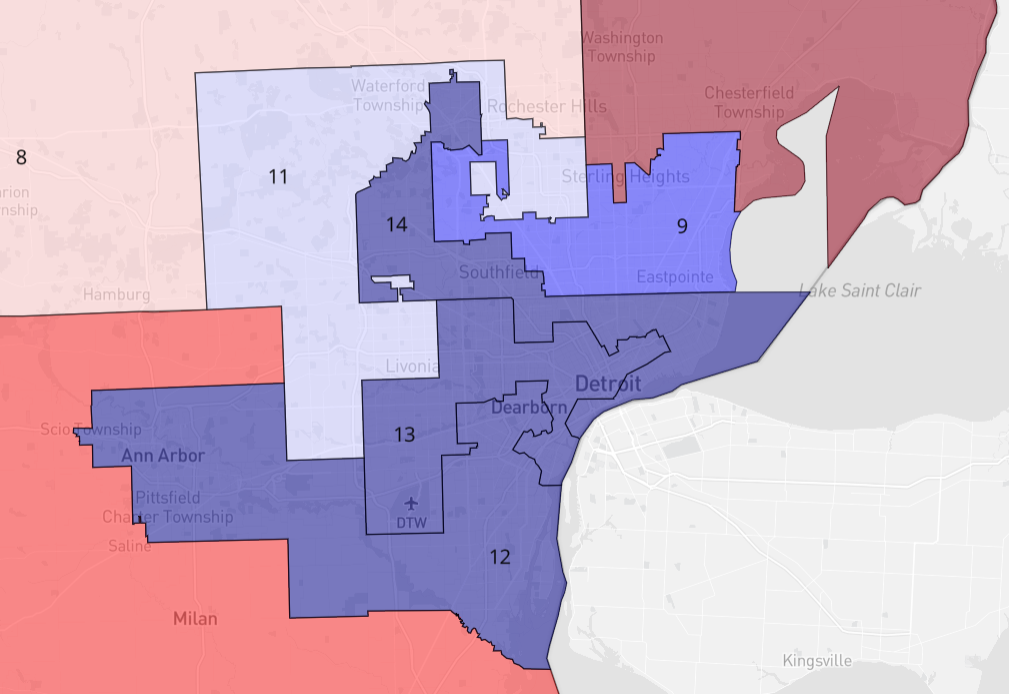

To make this concrete, consider the Detroit district previously held by Democratic Rep. Brenda Lawrence prior to 2022.[8] Lawrence first won election in Michigan’s 14th in 2014 and reliably won each general election with about 80 percent of the vote until she left Congress in 2022. The district was majority-Black and incorporated the part of the city where Lawrence grew up and attended high school, as well as the Detroit suburb of Southfield, where she served as the first Black female mayor.

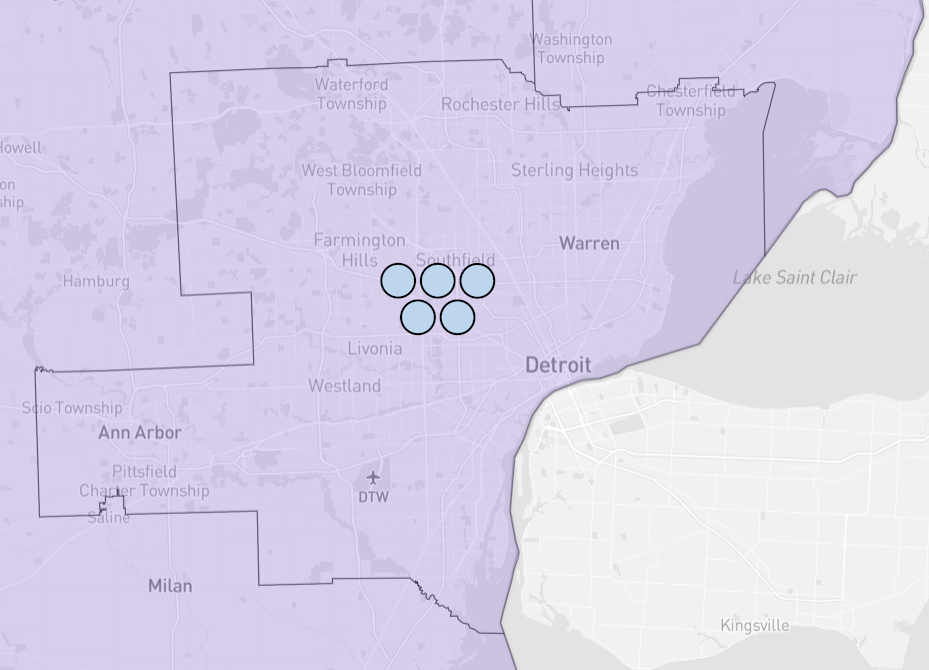

Under proportional ranked choice voting, the entire Detroit metro area would likely be a single district electing five winners proportionally, as shown in Figure 13. At first glance, that change might scare members with a strong connection to their district like Representative Lawrence had, but analyzing her election contest through the lens of a new system shows how it can actually be empowering for members like her.

Detroit’s 2020 district map and hypothetical combined five-winner district

A high turnout five-winner district in Detroit should attract about 2.25 million voters.[9] To win one of the five seats, a candidate would have to earn more than one-sixth of the total, or about 375,000 votes. So the question facing members previously representing a single-winner district here becomes whether they can earn that number of votes from the larger area.

In 2020, Lawrence earned 271,370 votes, almost three-quarters of the votes she would need within her district under a proportional ranked choice voting system. Without changing her campaign strategy at all, she would probably get more than under the new system, since her “safe” reelection contest drew very low turnout, and the new system would draw higher turnout. To earn the remaining 100,000 votes, she could campaign in any part of Detroit, not to mention the backup support she would naturally earn from other Democrats campaigning in the city. She would not suddenly need to run a big campaign across all of Detroit; she could win by confining her campaign focus to the neighborhoods she knows, and to her current constituents.

Lawrence and the other Detroit candidates would not run the same type of campaigns they do now, however. Grassroots campaigns could canvas in neighborhoods more organically, based on political priorities anywhere in the larger district, rather than staying within their prior district lines. Candidates would also be able to seek votes from communities that are not defined by geography. Lawrence, for example, was the only Black representative elected in Detroit in 2020, but 61 percent of Detroit’s Black population was spread among its other four districts. Many of those voters would likely be enthusiastic to vote for a Black representative from Detroit, and those votes add up to a very comfortable seat for Lawrence — and mean that she could enjoy greater influence and a stronger base throughout Detroit without having to run an exhausting citywide campaign.

In other words, if we had adopted proportional ranked choice voting to elect the U.S. House in 2022, Lawrence would have been well-positioned to keep her seat in Congress and would even benefit from a more empowering and dynamic campaign environment. Ironically, the change would have been less disruptive than the redistricting reform approach actually adopted in Michigan, which drove her out of her seat.[10]

Incumbents often fear a change to the underlying structure that allowed them to win in the first place, but, at the end of the day, candidates can win under proportional ranked choice voting if they run effective campaigns grounded in attractive policies that speak to the voters in their communities. Incumbents who have done the work to earn support need not fear a new system.

Of course, proportional ranked choice voting will not itself protect incumbents, nor will it artificially oust incumbents with genuine popular support. Although multi-winner districts would still be redrawn to equalize population every 10 years, those changes would be less disruptive, because votes earned across a larger area will matter more than the particulars of district lines. The time and money that incumbents spend protecting their districts every decade will be spent instead strengthening relationships with constituents and improving our democracy.

Notes

[1] As opposed to only in primary elections and the occasional special election.

[2] See Liz Ruskin, Palin and Begich both say ‘rank the red’ while diverging in style, Alaska Public Media (October 10, 2022), https://alaskapublic.org/2022/10/10/palin-and-begich-both-say-rank-the-red-while-diverging-in-style/. Note that Alaska is a small population state, only apportioned one representative, and so would likely retain the same system even if proportional ranked choice voting were adopted for House elections.

[3] Under the act, in states with partisan primaries, the default rule would be for each party to nominate a number of candidates equal to the number elected in the district. However, parties would have the right to nominate fewer than that, so long as they nominate at least two. In states with a “Top X” system (California, Washington, and now Alaska), the primary would advance twice the number to be elected, with a minimum of five. States like Louisiana, which hold no primary elections prior to the general election date, would hold a single-round, all-party, all-candidate general election by proportional ranked choice voting.

[4] See Tom Shales, Bill Maher: Back for More, Washington Post (August 2, 2004), https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/2004/08/02/bill-maher-back-for-more/ce223b2d-e55b-4358-a285-5da6a56a02ba/.

[5] The effective number of parties is not equal to the number of parties who win any seats in the legislature. Rather, it weights parties based on their relative strength using a formula, replicating how economists would measure competition among firms in an industry. The effective number is smaller than the absolute number; for example 11 political parties have at least one seat in the French National Assembly, but that Assembly has an effective number of 3 political parties.See Michael Gallagher, Electoral systems, Department of Political Science, Trinity College Dublin, https://www.tcd.ie/Political_Science/people/michael_gallagher/ElSystems/index.php.

[6] Yuhui Li and Matthew Shugart, The Seat Product Model of the effective number of parties: A case for applied political science, Electoral Studies 41 (2016) 23-34. Briefly, this model states that the number of effective political parties expected to win seats can be calculated by multiplying the total number of seats (435 in this case) by the average district magnitude (currently one, and about 3.7 under the Fair Representation Act), and then taking the sixth root of that product.

[7] Under the Fair Representation Act, states electing five or fewer winners elect statewide. States electing six or more winners must divide into districts drawn by independent commissions. The commissions are instructed to adopt a map that prioritizes district magnitude as follows: First, the map should have as few four-winner districts as possible; second, the map should have as many five-winner districts as possible. These preferences can only be overridden if necessary to avoid vote dilution of racial, ethnic, or linguistic minorities, or if necessary to avoid drawing districts likely to be swept by a single political party.

[8] The district was substantially altered by Michigan’s new independent redistricting commission after 2020, and Rep. Lawrence announced in January, 2022 that she would not seek re-election.

[9] About 450,000 votes were cast in the highest turnout congressional race in Michigan in 2020, about a fifth of 2.25 million votes.

[10] See Sarah Ferris, Rep. Brenda Lawrence becomes 25th House Democrat to retire, Politico, https://www.politico.com/news/2022/01/04/brenda-lawrence-25th-house-democrat-to-retire-526533 (Jan. 4, 2022), describing how the redistricting commission divided majority-Black parts of Detroit, “virtually eliminating her current seat.”

Contents

Part One:

The problems with

winner-take-all

Part Two:

Proportional ranked choice

voting explained

Part Three:

The benefits of proportional

ranked choice voting

- Universally competitive elections

- Fair representation for all

- Multi-racial representation

- Gender balance

- Better governance