Communities of color are underrepresented

It is effectively impossible to draw congressional district maps that include enough majority-minority districts to achieve fair representation through that mechanism alone, which is partly why people of color remain underrepresented in Congress.

Relying on districts for representation leaves out voters of color who do not live within the confines of majority-minority or opportunity districts. It makes it difficult to accommodate multiple minority groups or diversity within groups and does not work well for groups that move and/or grow between rounds of redistricting.

In Voting Rights Act cases, litigants sometimes prefer proportional or semi-proportional “modified at-large” systems over districts, and congressional elections feature nearly all the factors that make district systems inferior to proportional systems.

Race and ethnicity play central roles in American politics. The nation was founded by a collection of English and European colonists in a time and place that included both widespread race-based slavery and violent displacement of Indigenous populations. Racial and ethnic groups that immigrated to the United States also faced legal and social discrimination. The United States is racially and ethnically diverse, and often severely divided.

Much of American history concerns repeated struggles to overturn our nation’s shameful history of racism in its various forms, and we have made progress. Today, laws cannot explicitly categorize people by race and survive constitutional scrutiny. However, many modern laws and policies still have significantly unequal racial and ethnic impacts. In voting and elections, the best known relate to voting rights, like laws that require voters to show certain forms of identification or that purge names from voter registration lists. Less well-known is the significant racial and ethnic impact of our decision to elect representatives in a winner-take-all system.

The fight for equality necessitates a fight for a fair share of political power. Voting rights are and have always been central to the broader civil rights movement. However, vote denial is not the only way to diminish political power; vote dilution also disproportionately affects communities of color. Possessing the right to fill out a ballot that is counted in an election is simply not enough if that ballot does not carry the power to influence policy. In this sense, winner-take-all rules constrain the potential power of votes cast by people of color.

As a preface, two related points must be made clear. First, political power is not the same thing as descriptive representation, which refers to the demographic composition of Congress. Electing a legislative body that reflects the voting population is essential to a functioning democracy, and a disproportionately white Congress is strong evidence of disproportionate political power. But descriptive representation alone does not provide genuine fair representation. Rather, the question is whether the votes of communities of color are powerful enough to elect representatives who will work for them and promote their political interests.

Second, people of color have shared political interests, but they are not monolithic. To put a partisan point on it: They are not all Democrats, and the movement for equal political power cannot merely be a pretext for electing more members of a certain political party. That said, racial and ethnic groups should be able to vote for and elect representatives who are responsive to their interests, to the extent those interests are shared. In other words, the focus must be on the voters, not on elected officials or their partisanship.

Vote dilution in at-large elections

When President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act in 1965, no law required states to elect representatives from single-winner districts. Two states (Hawaii and New Mexico) elected multiple representatives statewide, and there was no legal reason other states couldn’t join them. All such at-large congressional elections followed a winner-take-all rule: A majority of the state’s voters had the power to elect every seat up for election, by use of “bloc voting,” in which each voter was allowed to cast as many votes as there were seats to be filled.

That context took on new significance in 1965 for two reasons. First, the U.S. Supreme had just issued a series of one-person-one-vote cases, which held for the first time that single-winner districts must all have equal populations. This corrected a flagrant abuse of districting whereby some districts had as much as ten times the population of others, exaggerating the voting power of people in the less populous, often rural, parts of states. However, it also rendered most congressional district maps illegal, and meant that if a state used districts, it would need to redistrict after every census to equalize their populations.

And second, in passing the Voting Rights Act, Congress outlawed many of the Jim Crow laws white powerbrokers had enacted, used, and manipulated to disenfranchise Black people and block their efforts to achieve equality under the law and equity in society. With the Voting Rights Act in place, white powerbrokers in many states quickly identified and seized on at-large elections as a way of maintaining white control of local legislative bodies.

The shift to at-large elections in Southern states is easy to explain: The Voting Rights Act outlawed efforts to stop Black people from voting, so white powerbrokers turned to at-large elections with bloc voting to ensure Black people’s votes were unable to elect anyone. Their logic: As long as white voters comprised the majority and could be trusted to vote for white candidates, voters of color would simply lack the numbers to win even a single seat.

In the wake of the Voting Rights Act, many local jurisdictions in the American South switched from districts to at-large elections. Members of Congress grew justifiably afraid that Southern states would make that switch in congressional elections as well, especially since it would give state lawmakers an excuse not to redistrict under the high court’s new “one-person-one-vote” equal population requirement.

Because of this context, the single-winner district mandate, passed in 1967, is best understood as a victory for civil rights. Congress passed it in part to prevent the inevitable vote dilution of communities of color that would follow if states began switching to at-large elections. The law did not eradicate the problem outside of congressional elections, though. To this day, a significant part of modern voting rights litigation takes place against jurisdictions that elect at-large officeholders, often with the goal of forcing them to switch to district-based elections.[1]

Districts per se, however, do not prevent vote dilution. They can either remedy or cause vote dilution. Even when they prevent severe vote dilution, they may place an artificial ceiling on representation. When voting rights advocates use districts as their main tool to ensure fair representation for communities of color, then success or failure comes down to the kind of districts that are drawn.

Majority-minority districts

Vote dilution involves robbing a group of voters of their power to elect, the thing that makes their vote effective. A cure, then, must ensure voters have the power to elect. In a single-winner election, the largest group of voters, usually the majority group, has the power to elect the winner. So, usually, the first step in addressing vote dilution through districts is to assess the demographics of the districts, and count the number of districts where a particular racial or ethnic group outnumbers all others.

Traditionally, the way to confer the power to elect to a minority group is to draw “majority-minority” districts — those in which the group’s eligible voting age population comprises a majority of the district. This strategy was pursued most forcefully in the 1990s, after Congress amended the Voting Rights Act in 1982 to address vote dilution, and after the US Supreme Court established the framework for vote dilution lawsuits in Thornburg v. Gingles in 1986. During the 1990-91 redistricting cycle, lawmakers adopted a dozen new Black-majority congressional districts in Southern states. All 12 elected Black representatives in 1992, and those wins were collectively responsible for 100 percent of the increase in Black representation in Southern congressional districts that year.[2]

Majority-minority districts, however, do not come without criticism or cost. In some places, creating these districts required drawing very strange shapes, pulling geographically disparate Black and Latino neighborhoods together with connecting ligature, sometimes spanning a single road. In fact, many of the absurd shapes redistricting reform advocates highlight to protest partisan gerrymandering are not, in fact, partisan gerrymanders; they are majority-minority districts drawn to comply with the Voting Rights Act — and its goal of fairer representation of communities of color.[3]

The more significant problem is the broader effect majority-minority districts have on legislative elections. Insisting on a rigid minimum population of voters of color may “pack” that population into a small number of districts, reducing their influence across the state as a whole. In the 2010-11 redistricting cycle, Republicans used majority-minority districts as a pretext for partisan gerrymandering. In that cycle, they packed Black voters into heavily majority-Black districts in order to minimize the number of Democratic-leaning districts, and then claimed they did so to comply with the Voting Rights Act.[4]

Using districts for effective representation means that the district map will determine, in advance of any votes cast, precisely how much influence voters of color will have in elections. The effects are lasting: Demographics often change over the course of a decade, but the districts stay the same. Even if a certain population increases substantially, that growth will not directly lead to more political power, at least not until the next round of redistricting.

Moreover, because each district elects a single winner in winner-take-all contests, districts are a poor fit for states with multiple substantial minority groups. Even if each group is populous enough to elect candidates of choice, it may be difficult or impossible to draw each into their own district if groups overlap geographically.

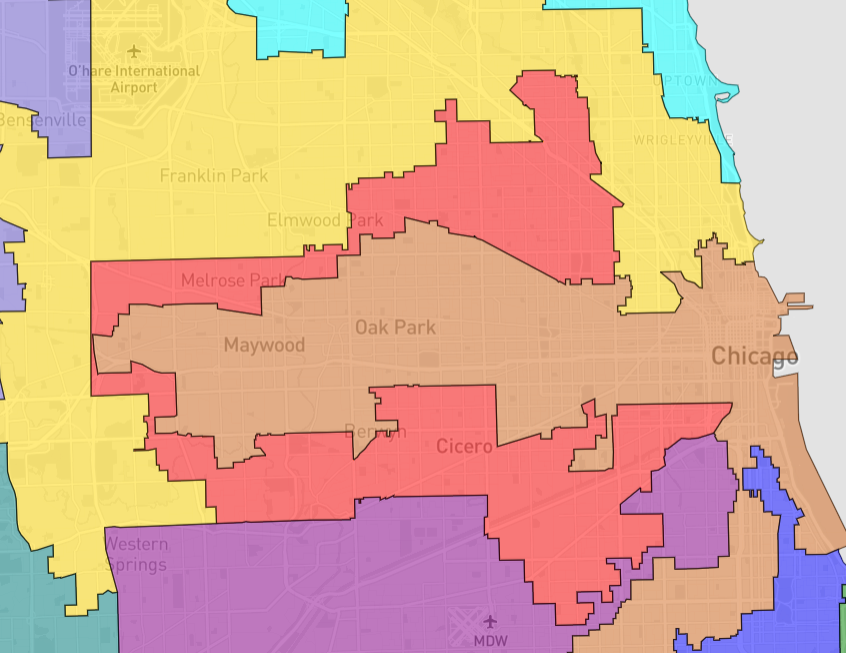

This is why Illinois wound up with its infamous “earmuff” district in Chicago during the 2010 redistricting cycle. The state’s 4th congressional district is often used as the poster child for gerrymandering, because of its bizarre shape. But it only looks the way it does so that it can connect two separate Latino-majority neighborhoods while snaking around the Black-majority neighborhoods in the state’s neighboring 7th congressional district. Districts prioritize geography — a poor fit for communities that are not geographically well-sorted.

Illinois’ “earmuff district”

Finally, using districts to achieve representation for voters of color leaves out all such voters who live outside the confines of the district. In places with racially polarized voting, these voters are hopelessly outnumbered and outvoted in every election.

A closer look at the makeup of districts drawn in the United States during the 2010 redistricting cycle demonstrates the shortcomings of districts as a means for representation. This cycle is instructive, because districts were drawn when the Voting Rights Act was still in full effect — and before the federal courts began chipping away at its protections.

The limited effectiveness of districts in practice

Table 2 summarizes the demographics[5] of the 435 districts drawn in the 2010-2011 redistricting cycle and the race or ethnicity of the representatives elected in 2012 in those districts.

The demographics of the elected representatives show that racially polarized voting remains the norm. The pattern is not perfect: Representatives of all races and ethnicities do win across all kinds of districts. But the pattern is clear nonetheless, reinforcing the majority-minority district’s utility for conferring the power to elect a preferred representative.

The statistics in Table 2 also belie a shortcoming of such districts: there are not enough of them. The district maps used in 2012 were adopted before the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the preclearance regime in Shelby County v. Holder. That means they had to be precleared by either the Department of Justice or by a three judge panel as not diluting the votes of any racial or ethnic groups.

Nonetheless, the overall number of majority-minority districts falls well below what would be needed for that mechanism alone to provide the power to elect a proportional number of representatives of choice. Figure 5 shows the overall proportion of eligible voters that identifies as one of these categories,[6] followed by the proportion of districts where each group is the plurality (either majority-minority or a coalition district in which they are the largest single group).

What’s more, no matter how many majority-minority districts a state may be able to draw, it will never include all members of the relevant community in a district where they have the power to elect candidates of choice. For example, Louisiana’s single majority-Black district, the 2nd, is represented by Black Democratic Rep. Troy Carter and previously by Rep. Cedric Richmond. About 333,000 eligible Black voters lived in that district in 2012. However, the state has more than 1 million eligible Black voters. That means that more than two-thirds of Black voters in Louisiana live in one of its five majority-white districts, all of which are safe for Republicans.

Black voters who live outside the state’s sole majority-Black district likely feel poorly represented in Congress. Some may feel “represented” by Carter, but they are no more his constituents than they are of the House’s other 434 members. Because Carter is not accountable to them, he cannot be relied on to represent their interests.

All told, under the districts used in 2012, only about 36 percent of Black voters across all 50 states lived in a majority-Black district. About 45 percent of Latino voters lived in a majority-Latino district. About 12 percent of Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) voters lived in the single majority-AAPI district (in Hawaii). On the other hand, 94 percent of white voters lived in a white-majority district.

Lessons from the Voting Rights Act

Although the debate between at-large and district elections ended for congressional elections in 1967, it rages on at the local level. At-large “bloc voting” remains a common way of electing local city councils, school boards, county councils, and so on. When these places grow and diversify, they face threats of litigation under the Voting Rights Act for vote dilution caused by this winner-take-all election method.

As a result, voting rights litigants and courts have thoroughly engaged in how to assess district maps for their ability to resolve vote dilution caused by at-large elections. The kind of analysis above — comparing population demographics to the demographics of particular districts — is exactly the sort of analysis that courts use to see whether a local or state district plan violates the Voting Rights Act.[6]

Sometimes, the parties to a lawsuit settle the case without going to districts but rather by adopting a proportional or semi-proportional voting method, and courts have found ways of determining whether proportional voting works to resolve vote dilution in this context. Over 100 local jurisdictions have adopted semi-proportional voting methods to resolve vote dilution lawsuits, and two cities, Eastpointe, Michigan, and Palm Desert, California, have adopted proportional ranked choice voting to do so.

Voting rights litigants seek proportional representation as a remedy for several reasons, including:[8]

- The community at issue is not geographically compact enough to be easily drawn into an appropriate number of majority-minority districts.

- The community is big enough to be able to elect candidates under a proportional method.

- The community is moving or growing, and a rigid district map may fail to reflect those changes over time.

- There are multiple minority communities, and districts may require excluding one group in order to include another.

- The community may be better able to recruit strong candidates jurisdiction-wide than from a single smaller district.

- The litigants want to avoid having to relitigate the issue during the next redistricting cycle.

All these factors plainly apply to congressional districts, with the possible exception of candidate recruitment — suggesting that proportional representation could be the right remedy for vote dilution in the U.S. House. That could be especially true of the final reason provided: to avoid having to litigate every redistricting cycle. Reliance on litigation to avoid racial and ethnic vote dilution has always been an awkward and imperfect tool, but that tool may not work at all for much longer. The federal courts have become significantly less favorable to voting rights litigants since former President Donald Trump successfully appointed three justices to the U.S. Supreme Court and more than 200 judges to other federal courts. The future of race-conscious districting, in other words, is in doubt.

The prohibition on winner-take-all at-large elections to Congress certainly represented an improvement for the voting power of communities of color. However, that action has proven itself to be wholly inadequate when compared to the use of a proportional voting method like proportional ranked choice voting.

Notes

[1] The Supreme Court established the elements of such lawsuits in Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986), which includes requiring a demonstration that the community at issue is sufficiently numerous and geographically segregated to comprise the majority of a single-winner district.

[2] Contours of African American Politics: Volume 2, Black Politics and the Dynamics of Social Change. United Kingdom, Taylor & Francis, 2017.

[3] See, for example, Michael Li of the Brennan Center attempting to make this point about the company “Resistance by Design” using majority-minority districts in its line of clothing featuring gerrymandered districts: https://twitter.com/mcpli/status/1363918500536926210?s=20.

[4] See Symposium: Bringing sanity to racial-gerrymandering jurisprudence, Anita Earls, SCOTUSBlog, https://www.scotusblog.com/2017/05/symposium-bringing-sanity-racial-gerrymandering-jurisprudence/, May 23, 2017.

[5] Measured by Citizen Voting Age Population as of 2012 estimates.

[6] As above, measured by Citizen Voting Age Population as of 2012 estimates.

[7] See, e.g., Bone Shirt v. Hazeltine, 336 F. Supp. 2d 976, 980 (D.S.D. 2004). In Bone Shirt, a case against state legislative districts in South Dakota, the federal district court noted that Native Americans constituted about 7 percent of the voting age population in the state, and therefore should have the power to elect between seven and nine of the state’s 105 legislative seats. Because that population only made up a majority of only four districts across both state legislative chambers, the plan violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. There are presently zero congressional districts in which Native Americans constitute a majority of the district by any measure.

[8] This list is based on a few prior similar lists. Voting rights activist Jerome Gray published a list of reasons to prefer modified at-large remedies in 1999, drawing on his experience in Alabama. Jerome Gray, Winning Fair Representation in At Large Elections, https://fairvote.box.com/v/Jerome-Gray-Booklet. A similar set of criteria was put forward by FairVote legal staff in a 2016 law review article. Spencer et. al, Escaping the Thicket: The Ranked Choice Voting Solution to America’s Districting Crisis, 46 Cumb. L. Rev. 377 (2016).

Contents

Part One:

The problems with

winner-take-all

- Lack of competitive elections

- Severe polarization

- Unfair representation

- Underrepresentation of communities of color

- Lack of gender balance