Multi-racial representation

Proportional representation means representation for all. A simulation of the Fair Representation Act, which would require proportional ranked choice voting for all House elections, showed that it would yield the equivalent of 30 new majority-minority districts nationwide.

A far greater proportion of voters of color would have a representative who is responsive to their community, including nearly all Black voters in the Deep South and nearly all Latino voters in the Southwest.

The ranked ballot would give communities of color a new tool to build power.

The new system would create space to peacefully mediate racial and ethnic divisions, making a genuine and functional multi-racial democracy more possible.

In 2017, the city of Eastpointe, Michigan, was sued for violating the Voting Rights Act. Eastpoint is 30 percent Black, yet no Black councilmember had ever been elected in a contested election. No one accused the city of intentional discrimination; rather, the city elected its council in winner-take-all, at-large elections, in which white voters greatly outnumbered and outvoted the city’s Black population every time.

In most vote dilution cases stemming from at-large elections, the problem is remedied by dividing the jurisdiction into districts. However, in Eastpoint, the parties agreed to instead adopt proportional ranked choice voting, becoming the first city to do so.[1] More than 100 towns, cities, school boards, counties, and other localities have ended Voting Rights Act cases by adopting semi-proportional methods, specifically cumulative voting and limited voting. These systems have a strong track record of success, leading to increased election rates for people of color, increased participation from candidates of color, and higher turnout from communities of color.[2]

An affected community might prefer proportional voting to districts for several reasons. Consider the following facts about congressional elections under single-winner districts:

- Communities of color are not geographically sorted well-enough to gain their fair share of representation through districts alone.

- The nation is increasingly diverse, and communities of color are increasingly difficult to encapsulate in a rigid set of district lines.

- Critically, representation through districts requires courts to actively enforce the Voting Rights Act, and the Supreme Court has consistently acted to limit such enforcement.

Proportional ranked choice voting gives communities a new tool with which to organize voters and achieve fair representation. Its lower election threshold promises a massive increase in direct, actual representation across the country. Additionally, rankings enable communities of color to build more powerful coalitions. Taken together, these elements offer hope for mediating today’s severe racial and ethnic divisions and realizing the vision of a functional and accountable multi-ethnic democracy.

The impact of a lower threshold for election

In single-winner districts, candidates who earn a majority of the votes are guaranteed victory. That simple fact underlies the reason for using majority-minority districts to achieve representation: If a community can turn out a majority of voters, that community will elect its candidate of choice.

In proportional ranked choice voting, the threshold for election is lower. If three candidates will be elected, then one who earns more than 25 percent of the votes is sure to win. If a community can turn out more than 25 percent of the voters in a three-winner district, it will elect its candidate of choice.

Consider Louisiana, which elects six representatives. Five of its districts are majority-white, and one is majority-Black. The sole majority-minority district is a jagged corridor encompassing most of New Orleans and several majority-Black neighborhoods to its west, as seen in Figure 18.

Louisiana’s 2022 district map

This lone district does not give Black Louisianans the voice they deserve. First, nearly one-third of voting age Louisianans are Black, so one out of six districts is insufficient from a purely numerical standpoint. Also, two-thirds of the state’s Black population live outside this district, meaning that most of Louisiana’s Black voters are systematically outnumbered and outvoted in their districts.

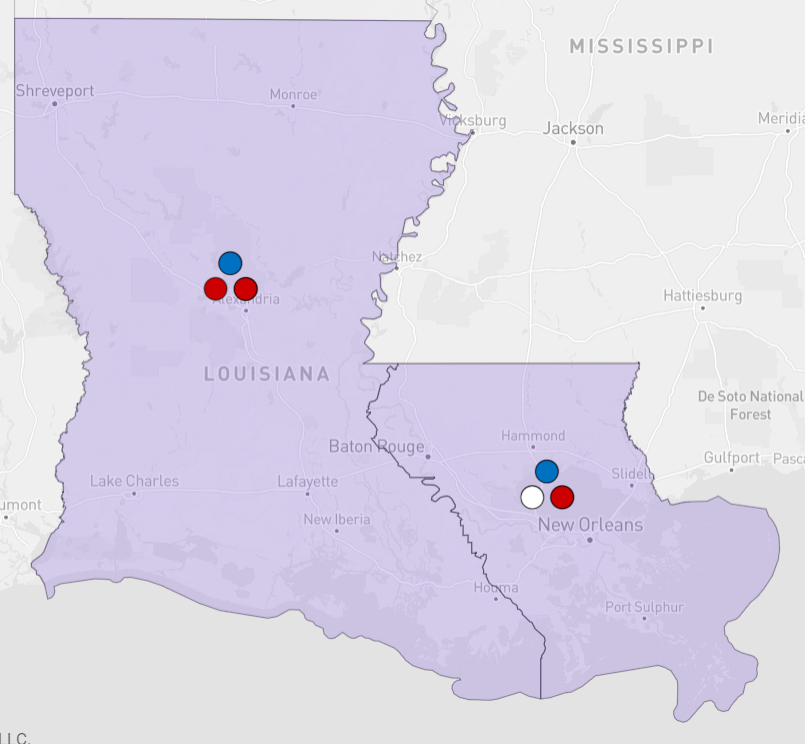

Now consider an alternative map. In Figure 19, the state is split into two districts of equal population: an eastern district and a western one that are roughly divided along county lines and the Mississippi River.

Sample multi-winner district map for Louisiana

This is how Louisiana might be districted under the Fair Representation Act, with each district electing three winners by proportional ranked choice voting. By voting age population, the western district is about 30 percent Black, and the eastern district is about 34 percent Black. With an election threshold of 25 percent, that is the equivalent of a Black-majority district in each half of the state, for two total. Every single Black Louisianan would live in a district where Black voters had the power to elect a seat.

In 2017, FairVote attempted an analysis of this sort for all 50 states using the multi-winner district maps generated by a computer program.[3] Those districts were drawn without regard to racial or ethnic demographics. The result yielded 15 new majority or plurality districts for Latinos, eight for Black Americans, six for Asian American and Pacific Islanders, and one for Native Americans, as Table 5 shows.

As a reminder, this is not only about how many members of a particular community will be elected to Congress. Of course, the more seats a group has the power to elect, the more members of that group are likely to be elected, but it is not a perfect fit. Rather, Table 5 shows the power held by voters of color that proportional voting in multi-winner districts would unlock. How communities use that power would be up to them, but their power would be far more commensurate with their numbers. In other words, proportional voting in multi-winner districts would make our system fairer.

Likewise, the districts would include a much larger share of voters of color. When representation is achieved with majority-minority districts, many members of the community gaining representation live outside of the majority-minority district, like the Black Louisianans who live among its five majority-white Republican districts.

With proportional ranked choice voting, a much larger percentage of Black Louisianans would live in a district where their vote contributes to the election of a candidate of choice. Under FairVote’s simulated maps, the number of eligible voters of color living in a district where their community has the power to elect would jump across every group, as Table 8 shows.

This effect is even more pronounced when considered regionally. In 2017, FairVote published companion articles on the impact of the Fair Representation Act for Black voters in the Deep South and Latino voters in the Southwest (defined as Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California).[4] In both cases, relevant communities had the power to elect at least one seat in almost every single district across their region.[5]

The above analysis relies only on the reduced threshold for election in larger, multi-winner districts, meaning that it would likely hold even if using a semi-proportional method like limited or cumulative voting. However, many of the most important benefits come from the ranked ballot and the round-by-round count.

The impact of ranked choice voting

In the 1990s, voting rights advocates pushed for replacing winner-take-all districts with semi-proportional voting, often citing many of the benefits above. The voting method most often called for was cumulative voting. In her 1993 Texas Law Review article, legal scholar Lani Guinier, the leading voice for proportional voting during this era, describes her principle of political fairness as “one-vote, one-value,” saying:

The only system with the potential to realize this principle for all voters is one in which the unit of representation is political rather than regional, and the aggregating rule is proportionality rather than winner-take-all. Semi-proportional systems, such as cumulative voting, can approximate the one-vote, one-value principle by minimizing the problem of wasted votes [emphasis added].[6]

However, the limits of semi-proportional representation have become apparent in the years since. Systems like cumulative voting allow communities outside the majority to elect candidates of choice only if they organize around the exact number of candidates they can elect. In other words, the election cannot include in-group competition. This has resulted, for example, in Democrats in Port Chester, New York, refusing to run more than one Latino candidate on their slate under cumulative voting, even as the town’s Latino population has grown.[7] In places where such candidates could not be suppressed, they sometimes split the community vote, resulting in the election of no candidates of color at all, as in the Amarillo (Texas) Board of Regents cumulative voting election in 2017, in which two Latino candidates ran and lost, despite collectively earning enough votes to win a seat.[8]

Fortunately, proportional ranked choice voting can achieve the benefits of these methods without their drawbacks.[9] In proportional ranked choice voting elections, the use of rankings by voters can have a substantial impact on representation, creating new tools that communities of color can use to build power.

As an example, consider the track record of single-winner ranked choice voting, also called instant runoff voting. This system is not proportional but operates just like proportional ranked choice voting as applied to the election of a single winner by majority vote. As such, it offers an experiment where we can control for the impact of the rankings and round-by-round counts independent from the impact of proportionality.

Cities that have adopted ranked choice voting have seen increases in election rates of candidates of color. In 2021, New York City used ranked choice voting in its municipal primary elections for the first time. The result: an increase in Black, Latino, and AAPI representation on the council and the largest proportion of women elected in the city’s history.[10] This reinforced a trend: Candidates of color and women of all races win at higher rates in cities with ranked choice voting than in those without it.

A 2021 report from FairVote assessed results and ballot data from nearly 400 such ranked choice voting elections and identified some reasons why candidates of color do better under the system:

- Candidates of color gain more votes between rounds than white candidates.

- Voters of color use more rankings than white voters.

- Candidates of color are not penalized by competition from other candidates of color.[11]

We should take care when applying lessons from single-winner ranked choice voting, especially in local and nonpartisan races, to proportional ranked choice voting for the U.S. House. The two are very different systems. But these dynamics do show how the ranked ballot and round-by-round count can improve representation compared to a vote-for-one system.Although harder to quantify, these benefits may go beyond effective ballot use and election rates to real responsiveness for otherwise underserved communities. Even if a group of voters has too few votes to elect a candidate of choice, the ranked ballot incentivizes candidates to care about what the group wants. Such a group can still have a candidate of choice, even if that candidate is unlikely to win, and other candidates will compete for the group’s second-choice support.

Consider, for example, Cincinnati’s use of proportional ranked choice voting in the 1920s. It elected nine seats with proportional ranked choice voting. At the time, the Black community’s voter share was just below the 10 percent election threshold. In 1927 and 1929, prominent Black community member Frank A.B. Hall ran as an Independent and instructed his supporters to withhold backup choices and vote only for him to protest the absence of Black candidates on the major parties’ slates. Hall did not win, but he demonstrated the power of the Black vote, placing 11th in a race for nine seats. The Republican Party, eager to attract more rankings, added Hall to its slate in 1931, and Hall became the city’s first Black councilmember.

From then on, Cincinnati Republicans consistently included a Black candidate in their slate.[12] Black representation on the council grew over the years as Cincinnati diversified — until it repealed proportional ranked choice voting in 1957 amid growing racial tensions as the modern civil rights movement gained steam, at which point no Black councilmembers won election for years. In fact, the repeal of proportional representation was cited as a contributor to racial unrest by the Kerner Commission, Lyndon B. Johnson’s Presidential commission that investigated the underlying causes of the 1967 race riots in Cincinnati and other cities, demonstrating how downstream effects of election methods can make the difference between peaceful resolution of polarizing issues and violence.

[13]Toward a genuine multiracial democracy

The 2020 census showed a large increase in the number of people of color across the United States, and — for the first time — a decrease in the white population. It showed that white people are no longer the majority in seven states and are no longer even the plurality in four. In short, it showed that our country’s multi-racial future is here.

Such demographic changes amid our racially polarized politics will surely escalate polarization. The polarization that culminated in the Civil War stemmed from a perceived threat to white supremacy and lasted into the Reconstruction period after the Civil War. It only abated once the perceived threat to white supremacy diminished due to the premature end of Reconstruction and the often-violent suppression of Black political power in the South.

If today’s increasing diversity escalates political polarization, then it could lead to another national disaster: another Civil War or a regime that again suppresses the power of groups of color, like in the 1870s. Or, it could lead to something new: a more peaceful and productive mediation of the country’s deep racial divisions. This option is plainly the best one.

In addition to increasing the voting power and the numerical representation of communities of color, proportional ranked choice voting can help white representatives recognize the value of those voices, even in conditions of severe racial polarization. Consider Chilton County, Alabama, which in 1988 adopted cumulative voting to remedy a Voting Rights Act challenge. The new system resulted in the election of the county’s first Black commissioner, Bobby Agee. His presence initially drew resentment, but over time he established enough credibility and expertise that the commission elected him chair for two consecutive terms. As occupant of the most powerful position in the county, Agee was able to improve all manner of policymaking for Chilton County’s Black community and to improve the county as a whole.[14]

Changing how we elect the U.S. House will not bridge our deep racial divisions on its own, but it will make mediation more possible. Proportional ranked choice voting will offer a clearer reflection of the nation’s diversity, and more representatives will have direct electoral incentives pushing them to look and listen. The benefits go beyond the proverbial voices being heard. After all, the U.S. House is a place of power. There, traditionally excluded voices will not only have more say in the national conversation but will also be better able to shape law and policy.

In this way, proportional ranked choice voting in the U.S. House can open the door to a genuine, functional multi-racial democracy in the United States.

Notes

[1] As of writing, Eastpointe is expected to stop using proportional ranked choice voting at the expiration of the consent decree in 2023, unless Michigan state law is amended to allow it in the absence of a court order. See Samuel J. Robinson, Legislation would allow ranked-choice voting in Michigan. In one city, it’s already happening, Michigan Live, https://www.mlive.com/public-interest/2022/03/legislation-would-allow-ranked-choice-voting-in-michigan-in-one-city-its-already-happening.html (March 9, 2022).

[2] FairVote, “Effectiveness of Fair Representation Voting Systems for Racial Minority Voters” (January 2015), https://fairvote.app.box.com/v/fair-rep-voting-rights.

[3] These maps and associated analysis are available at FairVote, The Fair Representation Act Report, https://www.fairvote.org/fair_representation_act_report.

[4] Here the “Deep South” was defined as Louisiana, Mississippi, Georgia, South Carolina, and North Carolina, while the “Southwest” was defined as Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and California. Rob Richie et al, “The Impact of the Fair Representation Act: African American Voting Rights and Representation in the Deep South,” https://www.fairvote.org/the_impact_of_the_fair_representation_act_african_american_voting_rights_and_representation_in_the_deep_south; Rob Richie et al, “The Impact of the Fair Representation Act: Latino Voting Rights and Representation in the Southwest,” https://www.fairvote.org/the_impact_of_the_fair_representation_act_latino_voting_rights_and_representation_in_the_southwest.

[5] In the Deep South, Black voters had the power to elect at least one seat in every district except a single district in northern Georgia. In the Southwest, Latino voters had the power to elect at least one seat in every district except a single district in northern Arizona.

[6] Lani Guinier, Groups, Representation, and Race-Conscious Districting: A Case of the Emperor’s Clothes, 71 Tex. L. Rev. 1589 (1992-1993).

[7] See Maya Efrati & Drew Penrose, “Ferguson-Florissant School Board Elections Improve with the Voting Rights Act,” FairVote (Dec. 1, 2016), available at https://www.fairvote.org/ferguson_florissant_school_board_elections_improve_with_the_voting_rights_act.

[8] Maya Efrati, “Local Elections in Texas Demonstrate the Power – and Limits – of Cumulative Voting Rights,” FairVote (May 19, 2017), available at https://www.fairvote.org/texas_cumulative_voting_rights.

[9] For a contemporary article recommending proportional RCV over cumulative voting, see Richard Briffault, “Lani Guinier and the Dilemmas of American Democracy,” 95 Colum. L. Rev. 418, 435-441 (1995). Guinier herself submitted a statement in support of a local effort for proportional ranked choice voting in San Francisco in 1996. See Pedro Hernandez (@pedrohzjr), Twitter (June 15, 2021), https://twitter.com/pedrohzjr/status/1404911619998683137.

[10] FairVote, New York City’s Ranked Choice Voting Rollout: Better Elections Yield Better Results, July 10, 2021, https://www.fairvote.org/new_york_city_s_ranked_choice_voting_rollout_better_elections_yield_better_results.

[11] FairVote, Ranked Choice Voting Elections Benefit Candidates and Voters of Color, May 12, 2021, https://www.fairvote.org/report_rcv_benefits_candidates_and_voters_of_color.

[12] See Robert Burnham, Reform, Politics and Race in Cincinnati, Journal of Urban History (January 1997), summarized by FairVote in Choice Voting and Black Voters in Cincinnati, http://archive.fairvote.org/rcv/brochures/Cincinnati_History_of_Choice_Voting.pdf.

[13] Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, 26, available at https://belonging.berkeley.edu/sites/default/files/kerner_commission_full_report.pdf.

[14] For example, Agee urged the commission to stop granting or denying road paving petitions on an ad hoc basis and instead adopt a neutral criteria-based process; the change led to more equitable road paving services for Black and white residents, and to more road pavings overall. See generally Richard H Pildes and Kristen A. Donoghue, Cumulative Voting in the United States, States,” University of Chicago Legal Forum: Vol. 1995: Iss. 1, Article 10. Agee eventually lost his seat in the 2016 commission election, owing to a combination of a split vote with a fellow Black Democrat Robert Binion and an increasingly Republican-leaning county.

Contents

Part One:

The problems with

winner-take-all

Part Two:

Proportional ranked choice

voting explained

Part Three:

The benefits of proportional

ranked choice voting

- Universally competitive elections

- Fair representation for all

- Multi-racial representation

- Gender balance

- Better governance